This is a common saying in the numismatic community – to the point of becoming a cliché – but it still bears repeating: buy the coin, not the holder. Today I will share with you the details of an unfortunate purchase, which hopefully should serve as a cautionary tale for fellow Chinese coins collectors.

Collecting is a demanding hobby; to stay ahead of increasingly deceptive forgeries, ingenious alterations or tooling, one needs to keep on learning the most intimate details of Chinese coins. It may sometimes be tempting to simply rely on the knowledge of others and buy a coin that is “out of our league” with a relative peace of mind. I would urge my readers to resist this temptation, though. Certificates from grading companies and the opinion of more experienced collectors should only help confirm your own judgement.

I recently bought a very rare and beautiful Chinese coin from a reputed Shanghai dealer. The Dragon dollar was in a PCGS holder, and the seller guaranteed that the coin had not been repaired or cleaned. The competition to buy this beautiful rarity was intense and I had all the reasons to buy with confidence, so I gave in to temptation:

The coin I coveted is a particularly interesting variety of the famous Kiangnan Pearl Scales Dragon (also known as Dragon with Circlet-like Scales). The dragon lost its tongue to weak strike, and has longer spines on its back and tail (江南戊戌珍珠龙长毛无舌版). Additionally, this particular specimen has a very special characteristic, that I had never seen before: the top of the 庫 character, probably due to a die chip, was perfectly rounded (圆头庫).

When I received the coin and could carefully examine its surface, I started to experience this uneasy feeling familiar to collectors: the left brain knows something is amiss, while the right brain emotionaly defends the purchase. The coin was definitely genuine, but I could not help but think the toning and surfaces had some unnatural quality to them. Pushed by intuition, I started researching the pedigree of this coin online; something I should better have done before buying! When I came across the picture below, my unease only grew:

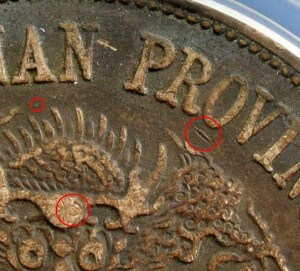

At first glance, it seemed unlikely that both coins were the same; the dragon dollar sold at the Shanghai Chongyuan auctions was heavily chopmarked. Both coins had a similar feeling to them though, and poring over the pictures, my troubled gaze feverishly jumping from identical circulation marks to the same rim nicks, I was increasingly convinced that it was indeed my coin, before it had been skillfully altered by a devious craftsman. I highlighted the details of interest below:

Carved right into the silver was the proof that the coin I bought was removed from its original GBCA holder, tooled with remarkable craftsmanship, artificially toned and successfully submitted to PCGS. Altering coins is a cardinal sin in numismatics: it is always done with the intention to deceive collectors and artificially inflate the value of a coin. I personally consider this practice tantamount to counterfeiting.

Circulation marks, nicks and scratches are the unique fingerprint of a coin. If on pictures two coins bear the same marks, there is only two possibility: either it is actually pictures of the same coin, or both are fake… As a more sinister example, please consider the picture below:

These two high level fake 1903 Fengtien dollars were spotted by reader Remetalk, using the same method I identified my altered coin. The coin on the left was listed at the April 2012 Hong Kong Auction, lot 21167, and graded NGC VF-20. The coin on the right was seen at the August 2012 Moscow Wolmar auction VIP №299, lot 1260. I spotted an identical fake in Beijing, graded VF details by PCGS.

With Chinese counterfeiters getting increasingly skillful at deceiving collectors and even world-class grading companies, it is more than ever necessary for fellow Chinese coins collectors to keep their eyes peeled, avoid impulse buying and always verify the pedigree of rare coins. Buy the coin, not the holder.

While american collectors put an emphasis on pristine coins, with “brilliant flashy mint state cartwheel luster” being an often seen eBay selling point for Morgan dollars, chinese collectors seem to like heavily toned or corroded coins. Why do chinese coins collectors like their coins “dirty”?

The reason is that chinese collectors don’t have the same relation with coins as their american peers.

Serious american collectors usually get their coins conserved, graded and hermetically slabbed, then store them securely in a bank vault or a safe. They don’t usually manipulate their coins, to avoid damaging them – they are actually fragile investment instruments. It is therefore important to get top grade, “problem free” coins to eventually sell them at an higher price than competing collectors with lower grade coins.

Chinese collectors most often store their coins in albums or coin capsules so they can be seen and touched, and won’t hesitate to test if a coin is genuine by making it ring against another silver coin (which will make the american collector wince). Chinese collectors value the link to the past that a coin represents – the many hands it went through, the many provinces it crossed from transaction to transaction. Manipulating the coin is just a continuation of its unique story, and therefore doesn’t decrease its appeal to chinese collectors.

It is therefore logical that toning is highly regarded in China: it is the outcome of a long aging process. Silver will naturally oxydize and react chemically to the substances it is exposed to, and depending of its alloy composition and environment, its colour will vary through a whole gamut of complex hues. A toned coin shows its history in the most vibrant way – its colourful surface is a unique, beautiful testimony of all the places and times it has gone through. That’s why it’s not treated as “filth” but respectfully called 包奖 (bao jiang).

A coin expert can tell from which part of China originates a toned, buried dollar. Soil composition varies in the different provinces, and it affects the chemical process accordingly: for example, silver yuan with a verdigris toning usually come from the South, and black coins from the Northern provinces. This adds to the narrative of the coin and makes it more attractive.

Since toning is such an aesthetic and desirable sign of old age, clever collectors or dealers have found out many creative ways to fake it. Methods range from the “organic”, like letting a coin bask in the sunlight on one’s window-sill or forget it in an enveloppe, to the somewhat gross (china ink, nose grease, cigarette smoke…) and the industrial (chemicals).

Most of these methods can be spotted – window-sill toning will make the coin surface look more dull, cigarette or chemicals usually leave the coin durably stinky. Artificial toning is designed to deceive buyers by dissimulating slight flaws (light cleaning, hairlines) or in the worst case hide retooling, harsh cleaning (acid prevents coins from toning) or as part of the artificial aging process for fake coins. Forgery is an industry in China, so artificial toning will almost always be chemical in that case.

Some black deposits around the legend or the rim of an otherwise white coin are an hallmark of fake chinese coins. If you look carefully, the residues usually look like some kind of paint or varnish. The surface of the coin is covered with this black substance, then it is washed to make it look like the surface of an old, cleaned coin. Some other coins are bathed in a chemical that leave the coin covered with verdigris like deposits, but unlike genuine buried silver dollars, such a forgery will actually reek of whatever was used to obtain this result.

The dust, corrosion and toning on a beautiful coin are aesthetic reminders of all the people who hold it before us and will hold it long after we are gone. For chinese collectors, feeling the weight of time in the palm of one’s hand is worth a premium.