In one of these internet message boards I frequent, a fellow Chinese coins collector produced pictures of a coin he had just bought from a dealer in Bangkok. I immediately identified a 英文大字珍珠龙: a nice variety of one of the most beautiful Chinese coins, the Kiang Nan dragon whose scales are ornate with pearls. This coin (often called “dragon with circlet-like scales” in English) was minted briefly in Nanjing at the beginning of the year 1898, before being replaced with a simpler design. There is several die varieties known, all very scarce.

Chinese characters on this particular variety are written with thicker strokes than usual, and the English legend is bolder as well. This concerned the new owner of this coin; did the unusual shape of the characters meant it was a forgery? I knew the design of the characters was normal, but finding a genuine 珍珠龙 (dragon with circlet-like scales) is a rare occurence, so the pictures still deserved a careful inspection.

The low resolution of the pictures didn’t allow me to get a good impression of the surface and relief of the coin. It looked like it had been dipped, but the details were convincing enough. The weight seemed a bit light (26.5 grams), but nothing egregious either. The picture of the edge was too blurry to be useful. At that point, I would have said it was a genuine, albeit badly cleaned coin. Nonetheless, something smelled fishy about it; something didn’t felt quite right, but for now I was unable to pinpoint it.

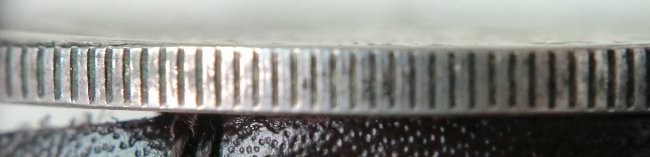

The next morning, higher resolution pictures were posted. Right upon looking at the edge, I knew the coin was fake. The reeding didn’t have the soft, rounded shape common to all the Kiang Nan silver dollars.

Now confident about the true nature of this coin, I had to announce the sad news to its owner: the case of the Bangkok pearls was closed. One day later, the Chinese coin collector posted a follow up. He had got confirmation from another coin dealer that the coin was indeed a forgery, and was able to return it for a refund. This case had a happy ending; not all do…

I bought a Fengtian dollar a few months ago, for the hefty sum of 40,000CNY – about $6000 USD. It was a very crisp looking, almost uncirculated, but unfortunately badly cleaned dollar. The edge was very convincing too, with a little bit of what looked like verdigris in some reeds. I was just somewhat intrigued by hints of a black substance around the legends and the rim. It didn’t look like carbon spots, more like some kind of ink. I wasn’t too worried though: quite often, people dipping coins are disappointed when they find out it doesn’t tone anymore, so they try to artificially colour the coin. Using chinese ink is not so uncommon for that purpose. Even with these issues, Fengtian coins with full details are very hard to come by, so I bought it.

As time went by, I found out a few minute difference between my coins and some similar ones sold in auction houses. The cloud below the rightmost claw of the dragon was not exactly the same shape than on the pictures. The left 口 of 器 was calligraphied slightly differently as well: on other coins, the right stroke is sticking out a bit at the bottom. One Manchu character on the reverse lacked a serif. Since these differences were very subtle, I thought it was maybe just another die variation. I searched for more pictures of genuine coins of that type, but I eventually was unable to find one looking exactly like mine: all of them shared the same features.

At that point it seemed less and less likely that my coin was genuine. I went back to the market where I had bought it, with the idea to get it assayed by expert coin dealers there, and to get my money back if they confirmed it was a forgery. Two of them examined it carefully and said they were not sure if it was genuine or fake, but that it looked convincing enough. The third one said it was probably genuine, but warned me he was not a specialist of the coins from this province.

I was not satisfied by these answers. I was about to leave, when I decided to try asking a last coin dealer. She was a nice elderly lady, and when I asked her if she thought the coin was genuine, she didn’t reach for her magnifying glass like everyone else. Instead, she simply took one of her coin, a British trade dollar, and hit my dollar with it. Then she hit the trade dollar with my coin. It didn’t sounded the same… That was definitely a bad sign, and I felt a bit ashamed to not have used this old trick myself before.

She then fetched a tiny portable weighing machine. The coin weighed 25.9 grams. One gram underweight. The verdict was clear: the coin was fake, as the kind old lady was now telling me. She also quickly checked if it was magnetic, but there was no real need at that point. While all of us, proud of our knowledge of chinese numismatics, were pondering if the coin was real or not by looking at the minute details of its surface, she found out the truth in the most elegant way. She just went back to the basics and worked it out from here.