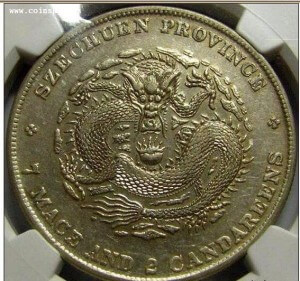

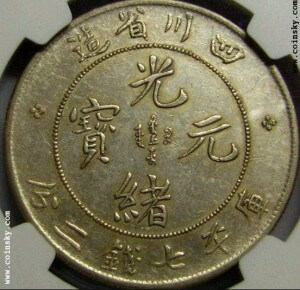

A good friend from Hangzhou recently contacted me regarding a Chinese coin he was interested in purchasing. It was a beautiful but rather expensive Szechuan coin (¥100,000 RMB or about $16,400 USD at the time of writing), and he was unsure about the deal.

The Szechuan dollar my friend was considering to buy was a high grade sample of the rare “库 not connected” variety (四川光绪剑毛龙无头车). It had sharp details and was graded AU50 by NGC, however the coin had clearly been cleaned and my friend hoped for a discount.

I browsed past sales results when I was struck by the similitude between the coin my friend coveted and a Szechuen dollar sold at the Jiuzhou 2012 Summer Auction (九州2012夏季机制币、纸币拍卖专场). At first, I thought that the coin graded XF details by PCGS had been re-submitted to NGC in a bid for a more favorable grade, but I quickly verified that the coins’ obverse were distinct.

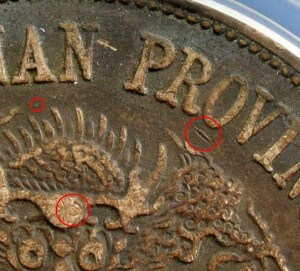

While carefully examining the reverse, I was troubled to find an identical scratch below the right side rosette. Despite the low resolution of the pictures sent by my friend, it was obvious this ought to be a circulation mark. Two coins of the same type often exhibit wear or weak strike in the same place, but identical circulation marks should never be observed: it would indeed imply both coins were randomly damaged in the exact same fashion while being handled by countless men and women through a century!

The scratches I highlighted on the picture above were damning evidences that both coins were very high level forgeries. The counterfeiters went to the trouble of striking different obverses, but were surprisingly lazy etching the same marks on the reverse. The replica is still stunning, and actually fooled two world-class grading agencies and the highly experienced Chinese coins collectors who bought them. It is especially troubling that without the inexplicable laziness of the counterfeiters, and a stroke of luck comparing pictures on the Internet, both fake coins would have most likely stayed undetected.

Once again, I will urge my dear readers to listen to their instinct when buying: if you are somehow hesitant about a deal, like my friend was, the best decision is often to walk away. It is also best to avoid buying cleaned or polished coins altogether, especially in high grade, as it is too convenient a camouflage for artificial aging.

This is a common saying in the numismatic community – to the point of becoming a cliché – but it still bears repeating: buy the coin, not the holder. Today I will share with you the details of an unfortunate purchase, which hopefully should serve as a cautionary tale for fellow Chinese coins collectors.

Collecting is a demanding hobby; to stay ahead of increasingly deceptive forgeries, ingenious alterations or tooling, one needs to keep on learning the most intimate details of Chinese coins. It may sometimes be tempting to simply rely on the knowledge of others and buy a coin that is “out of our league” with a relative peace of mind. I would urge my readers to resist this temptation, though. Certificates from grading companies and the opinion of more experienced collectors should only help confirm your own judgement.

I recently bought a very rare and beautiful Chinese coin from a reputed Shanghai dealer. The Dragon dollar was in a PCGS holder, and the seller guaranteed that the coin had not been repaired or cleaned. The competition to buy this beautiful rarity was intense and I had all the reasons to buy with confidence, so I gave in to temptation:

The coin I coveted is a particularly interesting variety of the famous Kiangnan Pearl Scales Dragon (also known as Dragon with Circlet-like Scales). The dragon lost its tongue to weak strike, and has longer spines on its back and tail (江南戊戌珍珠龙长毛无舌版). Additionally, this particular specimen has a very special characteristic, that I had never seen before: the top of the 庫 character, probably due to a die chip, was perfectly rounded (圆头庫).

When I received the coin and could carefully examine its surface, I started to experience this uneasy feeling familiar to collectors: the left brain knows something is amiss, while the right brain emotionaly defends the purchase. The coin was definitely genuine, but I could not help but think the toning and surfaces had some unnatural quality to them. Pushed by intuition, I started researching the pedigree of this coin online; something I should better have done before buying! When I came across the picture below, my unease only grew:

At first glance, it seemed unlikely that both coins were the same; the dragon dollar sold at the Shanghai Chongyuan auctions was heavily chopmarked. Both coins had a similar feeling to them though, and poring over the pictures, my troubled gaze feverishly jumping from identical circulation marks to the same rim nicks, I was increasingly convinced that it was indeed my coin, before it had been skillfully altered by a devious craftsman. I highlighted the details of interest below:

Carved right into the silver was the proof that the coin I bought was removed from its original GBCA holder, tooled with remarkable craftsmanship, artificially toned and successfully submitted to PCGS. Altering coins is a cardinal sin in numismatics: it is always done with the intention to deceive collectors and artificially inflate the value of a coin. I personally consider this practice tantamount to counterfeiting.

Circulation marks, nicks and scratches are the unique fingerprint of a coin. If on pictures two coins bear the same marks, there is only two possibility: either it is actually pictures of the same coin, or both are fake… As a more sinister example, please consider the picture below:

These two high level fake 1903 Fengtien dollars were spotted by reader Remetalk, using the same method I identified my altered coin. The coin on the left was listed at the April 2012 Hong Kong Auction, lot 21167, and graded NGC VF-20. The coin on the right was seen at the August 2012 Moscow Wolmar auction VIP №299, lot 1260. I spotted an identical fake in Beijing, graded VF details by PCGS.

With Chinese counterfeiters getting increasingly skillful at deceiving collectors and even world-class grading companies, it is more than ever necessary for fellow Chinese coins collectors to keep their eyes peeled, avoid impulse buying and always verify the pedigree of rare coins. Buy the coin, not the holder.

Reader Arun sent me pictures of the Kwang-Tung dollar below, seeking confirmation of its authenticity. While I could see the coin was fake at a glance, I also thought it could make a good case study.

When beginner or casual collectors attempt to detect forgeries, they will usually try to determine if the coin they have in hand looks similar enough to a known “good coin”, usually from an illustrated coin catalogue. The problem with this method is the pictures included in printed catalogues are mostly meant to help identify a coin type and therefore rather small; they do not expose enough details for this comparison process to be meaningful.

The Kwang-Tung dollar is especially ill-fitted for this approach. A lot of them suffer from weak strike, and it can be easy for the unaverted eye to mistakenly match the overall coarseness of a fake coin with the fading details of a genuine coin struck with worn dies.

Even using the high resolution picture above, an inexperienced Chinese coins collector may think both coins are identical. This is because most casual collectors will “read” the coin: instead of seeing that the shape of the lettering is different (much bolder on the fake coin), they will see the text on both coins is the same. More subtle details like the coin denticles are likely to be ignored, as a boring frame for the devices of the coin: the attention of the beginner will be focused instead on the dragon, which is badly struck on both coins and thus actually rather similar.

It is however entirely possible to see that this coin is fake without even examining its devices. The “grainy” aspect of the surface of our reader’s coin, and the many “bumps” I circled in red are clear indication that this coin was struck with low quality cast dies. Such dies suffer from a common defect, called gas porosity voids, which results of the expansion of gas entrapped during the metal handling or in the injection process. A coin struck using such dies will exhibit the lusterless, pimply surfaces typical of a low grade forgery.

If you ever find such a poor replica coin in a shop, it is a safe bet that you will not be able to find a genuine coin there…