Summer is nearing its end, and the Hong Kong auctions season begins. August is usually an interesting time for Chinese coins collectors, when rare coins are made available on the market and new prices are set.

I was browsing the catalogue of Rarehouse, when I was intrigued by one of the highlight of the auction. The denticles of the lot 1355, a rare Yuan Shih Kai pattern coin, bothered me. These teeth reminded me a lot of two other coins I have seen before.

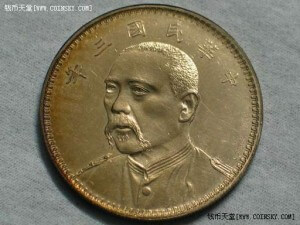

The first coin was introduced to me by a good friend, who was already in the midst of negociation with the owner and wanted my opinion about the deal. It was a beautiful specimen of an extremely rare Yuan Shih Kai dollar, with the signature of the famous Italian engraver L. Giorgi.

The price tag was not too high for this type – ¥200,000 CNY, or about $32,000 USD. This looked like a good deal, but I usually collect Imperial dragon dollars, so I decided to learn more about this type online.

That’s how I stumbled upon the sister of that coin. It was sold in 2005 on Coinsky, one of the largest numismatic forums in China, by the same collector from the Jiangsu province that now proposed to my friend the coin that sparked my curiosity.

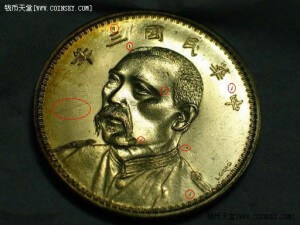

The identical scratches could not lie; as in previous articles, this was an indubitable proof that both coins were fake (click on the picture on the right for higher resolution).

Both replica coins also shared a strange defect, especially for pattern coins: the denticles on their obverse were really badly struck. Here is for comparison a picture of a genuine, graded pattern, lot 41099 at the upcoming Stack’s Bowers auction:

Small details matter: as you can see, the denticles are sharp and well struck.

My advice to fellow collectors looking forward to acquire rare and expensive Chinese coins this season would be to favour coins graded by PCGS. Raw coins can be cheaper, but if they end up being fake, you are on your own. For this kind of high level items, this can mean a $32,000 USD setback…

The plain edge of this “Fatman dollar” is not the result of circulation wear. Despite being called 光边 in Chinese, literally “bald edge”, it has not been shaved either. The usual reeding was simply never fully impressed onto the coin blank. If you look carefully indeed, you will notice a thin reeded part up to 6 o’clock. This Yuan Shih Kai dollar has actually suffered a random minting error called “broadstrike“.

Modern coins are machine struck. A blank is automatically placed above the lower die (or anvil die), fixed to the bed of the machine. The collar die is then brought up so as to encircle the blank, as the upper die (hammer die) is brought down with tremendous pressure. This cause the soft metal to flow like a viscous solid: prevented from escaping on the sides by the collar, it effectively gets imprinted by filling the engraving of the dies. If the collar was crenated, the edge of the coin will thus be reeded. This mechanical process was repeated about one hundred times per minute by the coining presses available at the time, and failures would inevitably happen sometimes. Broadstrike is caused by a particular problem: the collar die which is supposed to raise and surround the blank may get stuck due to some accumulation of debris or grease. If that happens, the metal unconstrained by the collar expands and increases in diameter during the strike. This results in a coin with all its design elements present, but an expanded shape: a broadstrike.

In the case of this “Fatman dollar“, we can deduce from the very thin reeding that the collar was partially engaged. The side with no reeding, completely unrestrained by the collar die, expanded the most. This type of coins is referred to as uncentered broadstrikes. This kind of error provides informations about the minting process. The traces left by the collar being on the reverse part of the edge means that the Yuan Shi Kai portrait was engraved on the hammer die.

Such misshapen coins are the result of random errors, but are accounted for by the mint. They are systematically destroyed when found during counting and packing the coins for dispatch. Very few of these coins indeed manage to slip through the combined vigilance of counting machines and human assayers to end up circulating. Even then, due to their suspicious appearance, they often are the first to get melted down for their precious metal content. It is therefore very rare for these unloved coins to reach the hand of a caring collector!

Die Variations: the 1914 Yuan Shi Kai Dollar (3rd Year of the Republic of China)

The Yuan Shi Kai dollar (or “fatman dollar“) is a very common coin. Liang Shi Yi (梁士诒), the former mint master of the Central Mint in Tianjin, remembered that for the first 9 months of production, 300,000 silver dollars were minted every day. Provincial mints were issued official dies from the central governement, and the new dollars were consistently up to standards.

This standardisation, allied to favourable circumstances, allowed the new coinage to successfully replace the dragon dollars and foreign trade dollars still circulating at the time. However, with years passing, several interesting die variations of the original 1914 dollar appeared and found their way into circulation. The most popular of these types are the “O” mint mark (O版) and the triangular yuan (三角圆) varieties. There has been much speculation about the origin of these special coins, which remains incertain.

A popular theory is that the “O” mint mark (O版) coins were minted in Shenyang (沈阳) in 1951 under the supervision of the People’s Bank of China (中国人民银行), for the exclusive use of the population of the southern provinces and ethnic minorities, who didn’t trust the Renminbi (人民币) currency. Popular lore also says that the triangular yuan coins would have been minted in 1949 to pay workers building roads in Tibet.

While there is some truth in these theories, they comport some flaws. In 1949, the new government banned the private possession of gold and silver. Older silver coins were to be exchanged at the bank for the new currency, the Yuan Renminbi still in use nowadays. In 1951 the People’s Bank of China had already withdrawn enough silver dollars from circulation that it did not need to mint any new one; it could have simply used those already in its possession.

What about the supposed location of their production? Shenyang was taken by the People’s Liberation Army on November 2, 1948. On November 3, the North-Eastern Communist Bank of China (中共东北银行) took control of the mint, and on November 8, the Shenyang branch of the North-Eastern Provincial Bank (东北银行) was established. The mint was immediately tasked to start producing silver dollars, in order to avoid a currency shortage in the province. The old 1914 dies of the original Yuan Shi Kai dollars were dusted off and put back to use.

In the records of the Shenyang mint (沈阳造币厂志), page 169, it is noted that the mint had to repair the old dies, “correcting a character” (改正一字) and “fixing the epaulette” (改修肩章) of the Yuan Shi Kai portrait. This description matches closely the changes observed on the triangular yuan variety: the 圎 (Yuan) character has been modified, and indeed the epaulette on the shoulder of Yuan Shi Kai is sharply struck. However, there is no mention of adding the “O” mint mark in the records of the mint. The existence of the “O” mint mark + triangular yuan (O版三角圆) variety would thus imply that the “O” mark existed prior to 1949, and the type “O” dies were simply modified along the normal dies.

A supporting evidence is that the original edition of “Illustrated Catalog of Chinese Coins” by Eduard Kann (耿愛德), published in 1953, included the “O” mint mark type (Kann 648) but not the triangle yuan. He compiled this catalog for the 47 years he stayed in China, before he “had to leave China in a hurry” during the takeover by Mao Ze Dong in 1949. The 1954 edition of the book was amended to include, amongst other additions, the triangular yuan variety. This shows the coins bearing the “O” mint mark were in circulation well before 1949, and that the triangular yuan coins were made after 1949, as confirmed by the records of the Shenyang mint.

If we dig further into the past, we can see from the archives of the mint (沈阳造币厂大事记) that it first minted Yuan Shi Kai dollars (1915) and Hong Xian commemorative silver coins (1916) under the supervision of the Central Mint. However, the records indicate that the mint issued new coins on 3 occurrences after that. On July 26, 1919, Zhang Zuo Lin (张作霖 aka Chang Tso-lin, warlord of Manchuria) renamed the mint as “Fengtien Arsenal” (奉天军械厂制造科) and minted both Yuan Shi Kai dollars and imperial copper cash coins. On January 13, 1921 and June 15, 1926, Zhang Zuo Lin ordered again some Yuan Shi Kai dollars to be minted at Shenyang to redress the finances of his provinces, strained by the successive wars against the Zhili clique and the Guominjun.

It is quite likely that the “O” mint mark was added to the old official dies in June 1926. Manchuria economy was in decline, and Zhang Zuo Lin had just appointed a new civil governor in March whose sole function was to supply his army with large amounts of money. The Fengtien dollar, which was quickly losing value against the Japanese gold yen, was debased. It would have made lot of sense to add a distinctive mark to the newly issued, debased coins to easily distinguish them from older issues which were up to standard.

Even if the popular theories were not too wrong about the place and time of minting of these varieties, we see now that these had actually nothing to do with Southern provinces or ethnic minorities. Both were produced in Shenyang primarily as emergency currency to try and shore up the ailing economy of Manchuria in difficult times: the O版 in 1926, as Zhang Zuo Lin was bleeding the province dry to conquer Beijing, and the 三角圆 in 1949, to start rebuilding the economy at the end of the Civil War.