Some readers have asked which dragon dollar is the most popular amongst collectors. The most famous chinese silver dollar from the late Qing era is most likely the Y31 silver dollar, colloquially referred to as “宣三” in China. It was minted in 1911 (3rd year of the rule of Xuan Tong) at the Central Mint in Tianjin. It was the last imperial coin issued before the regime was toppled by the Xinhai revolution. The design of this chinese silver dollar is considered by many collectors to be the most beautiful, and it is also the only imperial chinese coin bearing the “ONE DOLLAR” face value to have been circulated. While not rare by any measure, the Y31 dollar has seen its market value rise steeply in recent years due this popularity.

This dragon dollar was issued by the central authority, which means it had standardised weight, metal composition and design, but there exists nonetheless three die variations of this chinese coin.

The most commonly seen is called “浅版” in China, or “shallow strike version” (see below). Since it was struck with old dies, the details of the design are less clear in this version than in early ones. By looking carefully at the DOLLAR word on the reverse, one can see that the R was repaired by adding back a missing leg. It is labelled as “w/o Flame, w/o Dot” by PCGS:

The earliest version is called “深版“, or “deep strike version”. The details of this version are very sharp, the R in DOLLAR is still intact, and an additional spine which was lost to weak strike or die deterioration in subsequent versions is still visible at the tip of the tail of the dragon, across the cloud. While this version is only slightly scarcer than the 浅版, it is usually more expensive due to its popularity. This coin is labelled “Extra flame” by PCGS, due to the “additional” spine at the end of the tail of the dragon:

The last version is actually a restrike of the 浅版. In the years following the 1911 revolution, old dies were reused to issue new coins and avoid currency shortages. The already well worn dies of the 浅版 Y31 were briefly reused to mint the Y31.1 dollar, much scarcer than the earlier “official” issues. The only difference with the original dies is the addition of a dot after the word “DOLLAR“. Similar alterations were done to other revolutionary restrikes, like the 1904 Kiang Nan dollar with dots in the denomination.

Since the Y31.1 dollar is much more rare and expensive than other versions, many unscrupulous coin dealers or counterfeiters have tooled genuine dollars to add a silver dot, thus instantly doubling their profits. Most of these coins have been polished or cleaned first, though, to make the modification less obvious.

It is therefore advised to avoid buying cleaned or polished Y31.1 dollars. Genuine coins from the type “dot after dollar” (带点) were all made using the “w/o Flame, w/o Dot” 浅版 dies, so they have the same characteristics: fixed “R”, unclear details, and one spine less on the dragon tail. Uneven toning around the dot should be considered with extreme suspicion. A dot on a “Extra flame” dollar is a certain indication of tooling. Once again, be careful when buying chinese coins!

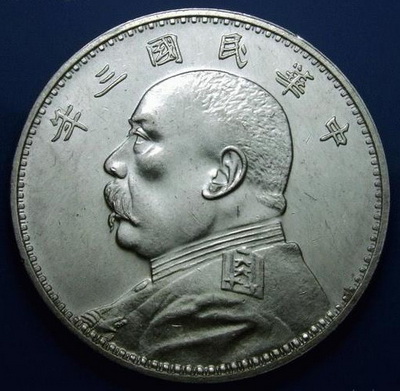

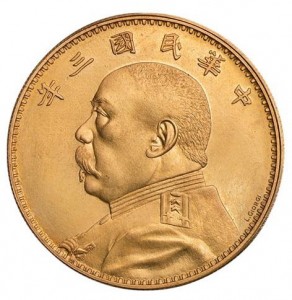

The Yuan Shi Kai silver dollar coin is one of the most commonly found Chinese silver dollar around the world, but paradoxically, there is few accurate information available about in English. Called 袁大头 in China (literaly “Yuan [Shi Kai] big head”), and “Fatman dollar” in the United States, this coin was designed to put an end to the chaotic state of the Chinese monetary system and further the political agenda of Yuan Shi Kai, who had just taken over the function of President of the newly born Republic of China.

Introduced for Christmas 1914, the Yuan Shi Kai silver dollar had a standardized purity (0.89000 silver) and weight (26.4000g, .7555 oz ASW). Like the previous central imperial issues, this new currency would have to compete against the chinese silver dollars already in circulation, foreign trade dollars, and resistance from provinces using primarily copper currency or paper money. The introduction of the Yuan Shi Kai dollar coincided with the withdrawal and melting of about 280 million dragon dollars. The remaining dragon dollars, whose fineness was not always up to the standard, could be exchanged free of charge for the new Yuan Shi Kai dollar in all Bank of China, Bank of Communications branches or official provincial banks.

These political measures helped the new currency to gain traction, but at the beginning of World War I, the Mexican dollar was still trading at a premium against chinese dollars, due to its use as a means of payment for exports. It is only after the War caused exports to plummet than the Yuan Shi Kai dollar was able to replace the Mexican dollar. The loss of the export markets also undermined the faith in the interprovincial paper money, which relied on external demand for local products, and caused the collapse of local copper currencies.

These economical factors contributed to the outstanding success of the Yuan Shi Kai dollar, which gradually penetrated even the most remote provinces of China. In 1924, a survey conducted by the Shanghai Bank found that of the estimated 960 million silver dollar in circulation in China, about 750 million were Yuan Shi Kai dollars.

Like the imperial dragon dollars before it, the Yuan Shi Kai dollar was minted in the Central Mint in Tianjin, and provincial mints were given official sets of dies. Due to its success, the “Fatman dollar” was minted during a longer time than any of its predecessor, and in much greater quantity, so the worn out dies eventually had to be retouched or re-engraved. This lead to a lot of dies varieties, some of which became very popular amongst coin collectors.

Scarce Die Variations: the 1914 Yuan Shi Kai Dollar (3rd Year of the Republic of China)

The 1914 Yuan Shih Kai dollar can be easily identified, even if you can not read Chinese, because it has only six characters on the obverse. All subsequent strikes have seven, due to the addition of the character “造” (made). This series offers some of the most interesting die differences.

The Central Mint in Tientsin issued some early pattern coins as a trial. Some of these coins have an ornamented edge, with a “T” like pattern (T字边), other have an edge similar to the one of the then popular Mexican dollar that this new currency sought to replace (鹰洋边, “Western Eagle” edge). These coins are the scarcest and most expensive.

Some of these trial coins also feature the signature of the italian engraver, L. Giorgi, who designed the coin. Most of the other die variations have been produced by provincial mints, and can usually be identified by looking at some details of the Yuan Shi Kai portrait. The design of the eyes and the 華 character (second starting from the right) are very different on the Kansu Mint die.

The coins issued by the Gansu Mint have a lower silver content than other Yuan Shi Kai dollar. They therefore circulated at a discount at the time, but ironically they are now more expensive than regular dollars due to their relative scarcity. The Gansu Mint also produced some coins with a custom die featuring the province name, which were quickly withdrawn by the government. This is now one of the most expensive versions of the Yuan Shi Kai dollar.

There is many more popular types amongst collectors, like the “O” die (O版), the “O die with triangular yuan character” (O版三角圆), or the “long leaves” dollar, all of which will be the object of another post…

The first modern, machine-struck silver coinage in China began in Guangdong in 1889. The new currency gaining in popularity, other provinces started to issue silver dollar coins. The Jiang Nan province (江南) was an early adopter and issued its first complete set of silver coins in 1897. This early set was minted in low quantities, with an original design which was quickly replaced by a more common one during the next two years. That makes the 1897 Kiangnan silver dollar a valued addition to a chinese dragon dollars collection. Sadly, the popularity of this coin amongst collectors made it a choice target for counterfeiters.

I recently saw a new kind of fake Lao Kiangnan coin floating around on online auction websites. It can easily be spotted by the little bumps around the rosette at the left of the dragon, and inside its coiled tail, as seen below.

Aside of the bumps, the coin is well struck and much more convincing than the usual crude forgeries found on these kind of websites. For comparison, here is what a real Lao Kiangnan looks like:

Any bumps on a machine struck coin should immediately raise suspicion; they are usually artifacts appearing during the process of casting. In this case, the coin is visibly struck, but most likely using a cast die – the bumps are the imprint of tiny bubbles trapped between the mold and the metal during the casting.