Sometimes it feels as if it is the coins that find the collector, rather than the way around. Last month, a reader contacted me intrigued by a dragon coin he had unearthed in the woods around Riga (Latvia). He was used to find Russian coins, but this time it was a superb Large-Mouthed Dragon from the Fung-tien province that made ring his metal detector.

When I saw the pictures he sent me, I knew immediately that this beautiful coin with hints of verdigris and earthy surfaces was a genuine Chinese silver dollar, buried alive over a century ago. The Large Mouth dragon is a very rare variety of the 1898 Fengtien dollar, hard to find even in China. How did such a rarity end up in Latvia?

At the turn of the century, both the Liaotung peninsula (which encompassed most of the Fengtien province) and Latvia were under Russian rule. So it is very likely that the coin somehow traveled in the pockets of Russian soldiers or the coffers of merchants, from Port Arthur in Russian Manchuria to the Imperial Port of Riga in Latvia. It was lost or hidden there for a hundred years before being found by our fellow reader.

After more than a hundred years and against all odds, that rare Fengtien coin found its way back home to Northern China after I forwarded the pictures to a fellow Chinese coin collector in Shenyang who was looking for this variety to complete his set of 1898 Fengtien coins.

In these lucky encounters lies one of the most joyful thrill of collecting. Yesterday, I serendipitously found two charming bracelets made of genuine 3.6 candareens silver coins from the Szechuen province – in Bourges, France, out of all place. I did not expect to find Szechuan dragons while travelling abroad! While these holed coins have already lost all numismatic value, these bracelets are still fascinating artifacts:

They were brought to France by an Admiral serving in French Indochine before the First World War. This kind of jewelry was common in China at the time: smaller silver coins were fashionned in buttons to fasten the coat of wealthy merchants, sequins on bridal headdresses, or bracelets adorning the wrists of beautiful women. Along with the two bracelets came a moving black and white photograph of their former owner, framed in carved fragrant wood. According to the handwritten note behind the picture, it was taken in Chongqing in 1906:

It is rare to have such a precise idea of the provenance of the coins we collect. These lucky bracelets which were brought to France in a military corvette will soon return home to China, in my pocket as I fly back to Beijing.

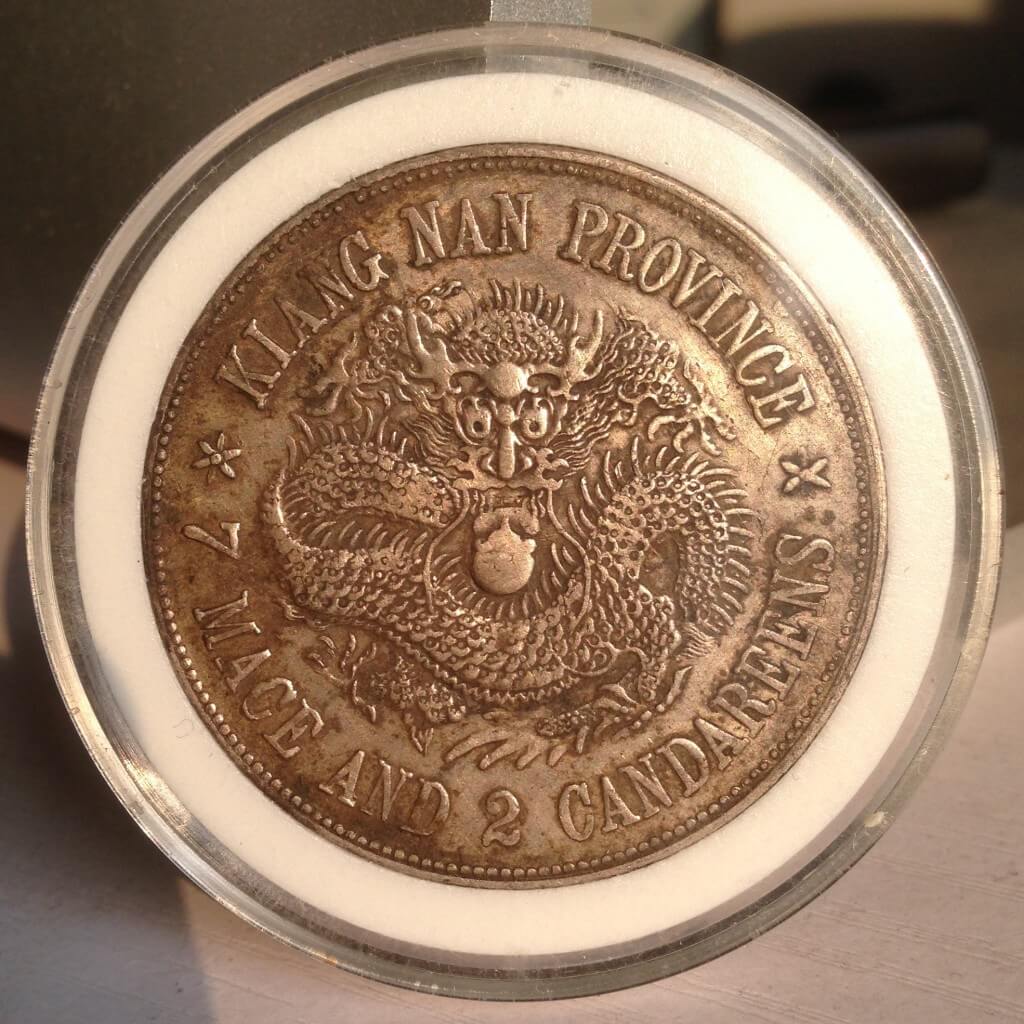

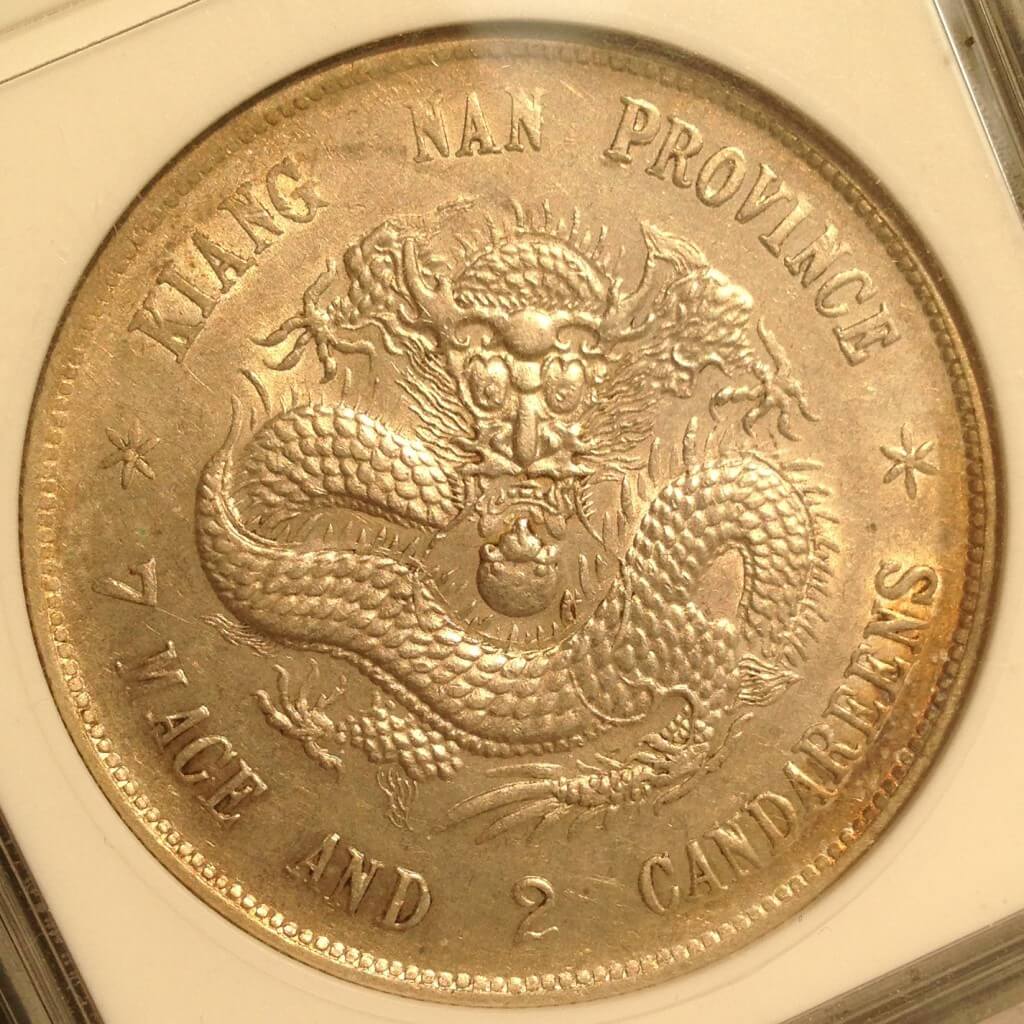

Basking in the diffuse light of the Beijing sky, five beauties from the Kiangnan province are quietly witnessing the end of another day. Everything under the setting sun is suddenly tinged with a nostalgic golden colour.

This glistening “Circlet-like scales” dragon is a rare breed. The doubled die turned its armour into a chainmail, delicately adorned with pearls. Below the K of Kiangnan Province, a lonely cloud has been struck in silver. The 江南戊戌珍珠龙K下多云 is an extremely rare variety, especially that well preserved. Most of the known specimen have already been worn down by a century of turmoil.

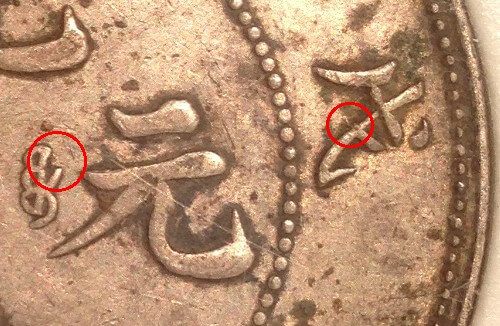

Collectors often wish coins could talk. This dragon would still be unable to tell them what it went through: he never had a tongue to begin with. His body covered in pearls is but skin and bones, meager and bristled with longer spines. The 江南戊戌长毛无舌珍珠龙 is a war-weary survivor, but it is still more easy to find than its cloudy cousin. This specimen hides more distinctive features on its back:

The rightmost Manchu character is broken, like the handle of a battered teapot. The “戊” character is also missing a stroke, left forever unfinished:

This particular combination of scars is uncommon; other coins of this type were usually struck with a complete date and Manchu inscriptions. The dragons with pearl scales are especially rare and beautiful, but other remarkable varieties were made the same year.

Endowed with a luxurious beard, the 江南戊戌大胡子龙 is a very popular variety amongst Chinese coins collectors. It is especially hard to catch one with all its exuberant pilosity left intact despite the passage of time.

The darting glance of its silver irides and the dot on its reverse are easily identifiable: this is a 江南戊戌凸眼龙满文中心点, a famous and desirable 1898 Kiangnan variety. However, it still has a subtle je ne sais quoi which makes it more pleasing to the eye than usual. After a while, the Chinese coins collector may realise that the dragon is framed within a circle of long denticles, conferring a unique harmony to the whole. While long denticles on the obverse are nice, long denticles on both sides are better:

Of course, this tasteful variety is extremely rare. There exists a similar “long denticles” variety for the last appearance of the Old Dragon, on the 1899 已亥 Kiangnan silver dollar:

Like the toning on this last Kiangnan dollar, the sky has already turned dark. Then all the charm is broken, and I leave the Kiangnan beauties to their contemplation.

This is a common saying in the numismatic community – to the point of becoming a cliché – but it still bears repeating: buy the coin, not the holder. Today I will share with you the details of an unfortunate purchase, which hopefully should serve as a cautionary tale for fellow Chinese coins collectors.

Collecting is a demanding hobby; to stay ahead of increasingly deceptive forgeries, ingenious alterations or tooling, one needs to keep on learning the most intimate details of Chinese coins. It may sometimes be tempting to simply rely on the knowledge of others and buy a coin that is “out of our league” with a relative peace of mind. I would urge my readers to resist this temptation, though. Certificates from grading companies and the opinion of more experienced collectors should only help confirm your own judgement.

I recently bought a very rare and beautiful Chinese coin from a reputed Shanghai dealer. The Dragon dollar was in a PCGS holder, and the seller guaranteed that the coin had not been repaired or cleaned. The competition to buy this beautiful rarity was intense and I had all the reasons to buy with confidence, so I gave in to temptation:

The coin I coveted is a particularly interesting variety of the famous Kiangnan Pearl Scales Dragon (also known as Dragon with Circlet-like Scales). The dragon lost its tongue to weak strike, and has longer spines on its back and tail (江南戊戌珍珠龙长毛无舌版). Additionally, this particular specimen has a very special characteristic, that I had never seen before: the top of the 庫 character, probably due to a die chip, was perfectly rounded (圆头庫).

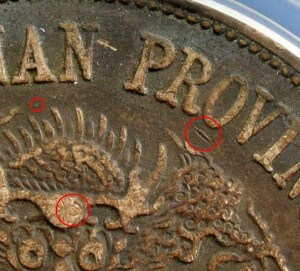

When I received the coin and could carefully examine its surface, I started to experience this uneasy feeling familiar to collectors: the left brain knows something is amiss, while the right brain emotionaly defends the purchase. The coin was definitely genuine, but I could not help but think the toning and surfaces had some unnatural quality to them. Pushed by intuition, I started researching the pedigree of this coin online; something I should better have done before buying! When I came across the picture below, my unease only grew:

At first glance, it seemed unlikely that both coins were the same; the dragon dollar sold at the Shanghai Chongyuan auctions was heavily chopmarked. Both coins had a similar feeling to them though, and poring over the pictures, my troubled gaze feverishly jumping from identical circulation marks to the same rim nicks, I was increasingly convinced that it was indeed my coin, before it had been skillfully altered by a devious craftsman. I highlighted the details of interest below:

Carved right into the silver was the proof that the coin I bought was removed from its original GBCA holder, tooled with remarkable craftsmanship, artificially toned and successfully submitted to PCGS. Altering coins is a cardinal sin in numismatics: it is always done with the intention to deceive collectors and artificially inflate the value of a coin. I personally consider this practice tantamount to counterfeiting.

Circulation marks, nicks and scratches are the unique fingerprint of a coin. If on pictures two coins bear the same marks, there is only two possibility: either it is actually pictures of the same coin, or both are fake… As a more sinister example, please consider the picture below:

These two high level fake 1903 Fengtien dollars were spotted by reader Remetalk, using the same method I identified my altered coin. The coin on the left was listed at the April 2012 Hong Kong Auction, lot 21167, and graded NGC VF-20. The coin on the right was seen at the August 2012 Moscow Wolmar auction VIP №299, lot 1260. I spotted an identical fake in Beijing, graded VF details by PCGS.

With Chinese counterfeiters getting increasingly skillful at deceiving collectors and even world-class grading companies, it is more than ever necessary for fellow Chinese coins collectors to keep their eyes peeled, avoid impulse buying and always verify the pedigree of rare coins. Buy the coin, not the holder.