This set of Chinese fantasy dollar is as famous as it is mysterious; in Chinese it is known as 光绪大婚纪念章, Guang Xu’s Grand Wedding commemorative medals. Mine came in the original box, along with a 1963 receipt and catalog from a Shanghai antique shop. These medals were definitely either intended as a wedding gift or commemoration: the dragon and phoenix, symbol of the union of the male and female principles, surrounded by the auspicious eight “double happiness” characters (八喜) are unmistakably characteristic. Every other fact about this set is however shrouded in mystery.

Both medals can be found in Colin R. Bruce’s Unusual World Coins standard catalog with references M119 (dragon) and M197 (phoenix). Most fantasy dollars are undated, but fortunately those are: 光绪乙酉年, or 1885. These medals are also exceptionaly well struck, with reeded edge and cartwheel luster usually typical of the products issued by a State mint.

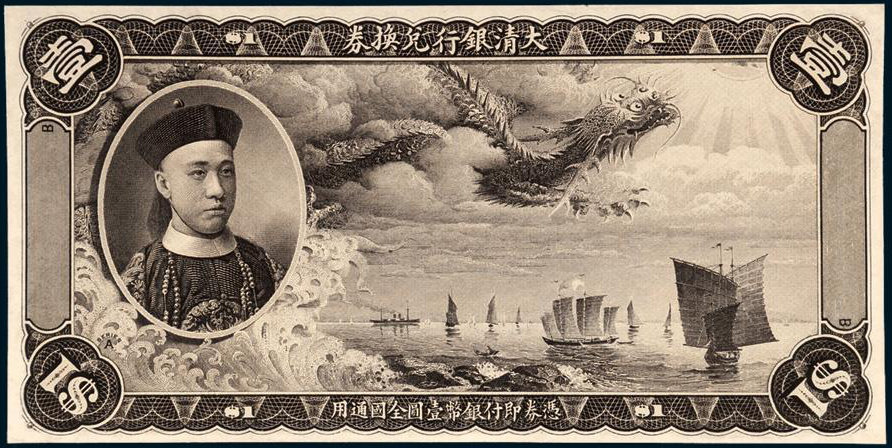

In English-language catalogs, the coins are said to depict “Empress Yun Lu” and either Emperor Dao Guang or Guang Xu. The obverse of the dragon medal does indeed bear the effigy of a Qing dynasty nobility, and it is generally assumed to be an Emperor by both Chinese and English numismatists alike, but this portrait was eerily reminescent of a late Qing Era banknote to me (see below).

Comparing the note and the coin leads to a puzzling conclusion: the obverse of this fantasy coin is actually a faithful reproduction of the official portrait of Regent Prince Zai Feng ! Since this banknote was issued in 1911, the set of medals can not possibly have been made in 1885, but only after the fall of the Qing dynasty. This supports the rumor mentionned in Bruce’s catalog that the set was actually minted in Shanghai during the 1940′s.

The identity of the woman depicted on the obverse of the phoenix medal is even more mysterious. English catalogs call her “Empress Yun Lu”, despite the fact there was no Empress or Consort named Yun Lu during the late Qing dinasty.

The closest match may be Empress Long Yu, which was chosen by Empress Dowager Cixi as the wife of Guang Xu in 1888. This is a major inconsistency if those 1885 dated medals actually do commemorate the Grand Wedding of Emperor Guang Xu.

Meanwhile, most Chinese collectors assume this noble woman is actually Empress Cixi, which is not very consistent with that hypothesis either.

With so many inconsistencies, it is likely both narratives are wrong. I would like to propose a new hypothesis as to the nature of this mysterious set. The male figure depicted on these coins can be identified as Prince Zai Feng without ambiguity; assuming that the mint did not confuse his portrait with the one of Guang Xu, this is a very interesting clue. I first thought this set could have been made for Prince Zai Feng second marriage with Lady Dengiya in the 1920′s. However Lady Dengiya does not resemble the portrait on the obverse of the Phoenix medal. Issuing medals bearing his image for his own wedding also does not fit with the character of Prince Zai Feng, who did not like power and its pomp.

To further invalidate this thesis, the five-clawed dragon on the reverse — appanage of the Emperor — would also be unsuitable for a Prince.

There was however another person who could legitimately use the five-clawed dragon symbol, loved Court sumptuosity, could have access to a State mint and had a special relationship with both Prince Zai Feng and Empress Dowager Cixi: the Last Emperor, Pu Yi.

Kann erroneously assumed that the 1923 Dragon and Phoenix dollar commemorated the Grand Wedding of Emperor Pu Yi, due to the connotations of the Dragon and Phoenix theme. It was actually an early coat of arms of the Republic of China, which was quickly forsaken for its similarity with traditional Imperial imagery. Please note however that the dragon on the 1923 dollar below have only four claws. Could Kann have heard of commemorative coins issued for Pu Yi’s wedding and simply reached a hasty conclusion?

Prince Zai Feng was Emperor Pu Yi’s father, and it was Empress Dowager Cixi who chose Pu Yi as Emperor Xuan Tong in 1908. He would therefore have had excellent reasons to honour them both on commemoratives medals offered as gifts to the prestigious guests attending his lavish wedding on December 1st, 1922. This hypothesis would conveniently explain the purpose of this set, the use of the Imperial Dragon pattern, and the choice of the portraits depicted on the obverse. The only missing detail would then be the date inscribed on the coins, 1885. Maybe a kind and erudite reader could contribute their idea about the signification of this date?

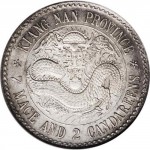

The first modern, machine-struck silver coinage in China began in Guangdong in 1889. The new currency gaining in popularity, other provinces started to issue silver dollar coins. The Jiang Nan province (江南) was an early adopter and issued its first complete set of silver coins in 1897. This early set was minted in low quantities, with an original design which was quickly replaced by a more common one during the next two years. That makes the 1897 Kiangnan silver dollar a valued addition to a chinese dragon dollars collection. Sadly, the popularity of this coin amongst collectors made it a choice target for counterfeiters.

I recently saw a new kind of fake Lao Kiangnan coin floating around on online auction websites. It can easily be spotted by the little bumps around the rosette at the left of the dragon, and inside its coiled tail, as seen below.

Aside of the bumps, the coin is well struck and much more convincing than the usual crude forgeries found on these kind of websites. For comparison, here is what a real Lao Kiangnan looks like:

Any bumps on a machine struck coin should immediately raise suspicion; they are usually artifacts appearing during the process of casting. In this case, the coin is visibly struck, but most likely using a cast die – the bumps are the imprint of tiny bubbles trapped between the mold and the metal during the casting.